Copyright Notice: This article is Copyright AI Factory Ltd. Re-use of it may be used with the direct permission of AI Factory Ltd.

October 2024 saw a historic event that probably passed by many people's attention: the WCCC (World Computer Chess Championship). This first began in August 1974 in Stockholm and was held every year for 50 years, concluding with the final championship, along with a with a special event to mark the history, in October 2024 in Spain. That's half a century that witnessed remarkable changes in AI.

As it happened, I was quite well-placed to contribute documenting of this event, as I had a minor foothold in its history. My own Fortran chess program, Merlin, was created as a student project in 1976 and had played and drawn against the program Beal that came 5th in that 1974 event, as well as beating a reduced version of the then U.S. champion chess program Belle. I had also competed against two of the 1974 WCCC programs in the European Championship in 1979 with my program Rasputin. The World Championship in 1974 and the ACM Chess tournaments had been an inspiration for me. In consequence, over the years, I had also met a number of the key authors from this period.

This is my personal log of this extraordinary event, first begun as I was journeying to attend it.

Additional thanks to Jonathan Schaeffer for his contributions to the article.

Prelude

A Friday late October found me embarked on a multi-hop journey to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. This was a venture way outside my normal worldwide travels, but this was a special trip as it marked the end of a very important era in AI, that I had been involved with for over 50 years. For that reason I had to be there, despite it competing with my significant schedule running AI Factory. I had met and briefly worked with some of these pioneers, but for many years I had just studied their work and followed their competitive progress in Chess, but from afar.

However, at this particular moment my connecting flight had been cancelled and I was stuck in Barcelona, so I chose this moment to start writing this article, as I awaited my very late replacement flight.

This was to be the 50th anniversary, and final act, of the WCCC (World Computer Chess Championship), first held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1974. The event had mirrored the Cold War chess rivalry that peaked in 1972 when Bobby Fischer defeated Boris Spassky, an encounter that symbolised the West's first triumph over the Soviet Union, which had dominated human chess for decades with a string of world champions. The WCCC brought together a highly multinational line-up of programs from the Soviet Union, USA, Britain, Canada, Austria, Hungary, Switzerland, and Norway. At the time, Western victory was widely expected, but in a reversal of the human chess result, the Soviet Union triumphed with their program Kaissa. It was their first and last win in the competition.

From 1974 and later WCCC events. Left to right: David Slate, Fred Swartz, Victor Berman, ; Mikhail Donskoy, ; Don Beal, Ken Thompson, Monty Newborn and Mikhail Botvinnik

Why do this?

Apart from any political overtones, why was this event and the 50 year era important?

Given its title, one might not expect the WCCC to spark much public interest today. After all, we are now so accustomed to carrying immensely powerful portable computers in our pockets — in the form of mobile phones — that can run chess programs capable of beating 99% of all human players. Against that backdrop, such a tournament might appear rather unremarkable.

However, computer chess has been a powerful and important driving force in the development of AI for some 70 years. It has been responsible for pioneering AI techniques that laid many of the foundations of modern artificial intelligence. It has also provided a driving force for talented engineers to divert to become engaged in AI, by providing the compelling challenge of making a computer just play at a credible level of this difficult game. This was also somewhat accelerated by a sheer raw competitive spirit. There is nothing like direct competition to drive zealous endeavours!

After 50 years, however, the WCCC was drawing to a close. Advances in processing power, coupled with the maturity and depth of AI techniques developed in part through chess, meant it was no longer the primary testing sandbox for new AI methods (and hadn't been since shortly after the 1997 Deep Blue match with Garry Kasparov).

Another factor was the loss of a meaningful competitive edge: grandmasters could no longer provide insightful commentary or criticism of the games. The reason was simple — computer chess had reached a "god-like" level of performance, with top programs rated at around ELO 3645. For comparison, the highest-rated human player in history, Magnus Carlsen, has a peak rating of 2882. If he were to play such a program over 100 games, ELO maths suggests he would expect to lose 99 and draw just one.

Finally these programs gravitated to the commonly expected conclusion, that chess was a likely theoretical draw. The previous competitions were indeed dominated by draws. That was a pointer to suggest that this competition was now in its twilight years as attention switched to other games and other areas of AI.

AI after Chess

AI has however since marched on over the last 8 years with some extraordinary advances, with games such as the oriental game Go, flagged as "too hard" for computers to challenge the supremacy of humans to play at the highest level, now elevated by deep learning programs to super-human performance. This event became exposed to the public by the historic defeat of Lee Sedol by AlphaGo in 2016, an event that flooded public media.

What the public will have missed was the then follow-on comprehensive dethroning of AlphaGo by the generic game solving AlphaZero with a 90% win rate. Humanity had been completely deposed as a source of the highest levels of Go play. Then came MuZero, whereby a single program could learn to play super-human Go, chess, and shogi without even being told the rules of the game! Now we have the ground-breaking LLMs, which have now grabbed so much of the public attention and are expected to radically reshape the future of human history.

Other types of games and puzzles have been conquered by AI, including those of imperfect information and stocasticty (e.g., poker and Scrabble), natural language skills (e.g., crossword puzzles and Jeopardy!), and video games (e.g., Atari games and Gran Turisimo).

The Reunion

This final act of the WCCC offered a rare opportunity to reunite the pioneers who had laid the foundations for so much of AI over the past 50 years. As a member of the ICGA (International Computer Games Association, previously the ICCA "Computer Chess") for more than 45 years, I felt personally connected to the occasion and began reaching out.

The original Stockholm tournament belonged to a very different era. Back then, moves were relayed by telephone to and from multi-million-dollar computers scattered across the globe, rather than from on-site machines networked together for automatic play. Programs were often developed on punch cards, not through online editors.

There was no internet then — a fact that now feels almost impossible to imagine. This made it all the more challenging to contact those involved in the 1974 event, most of whom, one would assume, were long retired. I began by contacting Jonathan Schaeffer, then president of the ICGA and head of the event. My first question was, "Have you contacted Mikhail Donskoy?" — the lead programmer of the Soviet team's winning program Kaissa. Sadly he had since passed away. Happily, the team leader for Kaissa, Vladimir Arlazarov, was successfully reached.

Others proved harder to track down. It took quite some time before Don Beal, author of the program Beal, was finally contacted. I had tried colleagues and even Queen Mary University of London, his final lecturing post, but without success. Fortunately, he independently got in touch with Jonathan Schaeffer shortly before the event.

Some key players from the 1974 competition could not be found at all, including John Birmingham, author of the UK program Master. Others, though located, had long since retired and were unable to attend. Age had taken its toll on some, whereby international travel was not possible.

In the end, the final line-up of attendees from the 13 programs that competed in the 1974 Stockholm event included Vladimir Arlazarov (Kaissa), Monty Newborn (Ostrich), and Don Beal (Beal). To this was added a distinguished roster of names from the wider history of computer chess, including Tom Truscott (Duchess), Tony Marsland (WITA/AWIT), Murray Campbell (Hitech; Deep Thought; Deep Blue prototype), Feng-hsiung Hsu (Deep Thought; Deep Blue prototype), Nenad Tomasev (AlphaZero), Richard Lang (Chess Genius; Mephisto), and David Levy — the latter probably the most recognisable public figure in computer chess. Levy's résumé includes being director or key organiser of around 20 computer tournaments, serving as ICGA president or vice-president from 1986 to 2018, and authoring some 40 published books.

It was, without doubt, a rich and historic assembly of some of the most significant figures in computer chess.

The Preliminary Event

After a long journey — marked by a missed connection, hours of waiting in airports, and a final bus ride into Santiago de Compostela late at night — I finally arrived at my hotel on Friday. The event was due to start the next day.

The tournament was hosted as part of the ECAI (European Conference on Artificial Intelligence). The choice of location felt somehow fitting: Santiago de Compostela is one of the world's most famous pilgrimage destinations, its history deeply bound to the Camino de Santiago ("Way of St James"), a network of routes that has drawn travellers since the early Middle Ages. In modern times, it became a perfect metaphor for this gathering — drawing together many of the key figures from the history of computer chess for an opportunity to honour, meet, and engage with one another. This far-flung community had been brought together to celebrate the close of a significant era. Such a reunion might not have even been possible had it been delayed by a few more decades.

So, perhaps like pilgrims of computer chess, we converged on this historic venue from every corner of the world!

The weekend began with the WCCSC (World Computer Chess Software Championship), a two-day contest run under a level-playing-field Swiss system, where each program operated on similar on-site machines. It was held at the university campus to the west of Santiago de Compostela, tucked away in a small room in the School of Communication Sciences — where the ECAI conference was also hosting tutorials.

From left to right in foreground: Carol Campbell, John Hamlen, Jonathan Schaeffer, David Levy and Erdogan Gunes

After a pleasant walk through the historic streets and past the cathedral, I arrived at this first venue. In this modest room, program authors sat opposite each other at student tables, running their programs and chatting about the games. Among them was, of course, Jonathan Schaeffer, and also David Levy — for whom I had worked on Cyrus Chess and created a checkers program for French Thomson computers. I had not seen David in over 20 years, our last meeting being at the 2002 Computer Olympiad in Maastricht.

Andrea Manzo on left and Jaap van den Herik on right

Old acquaintances were renewed, new contacts made, and the second part of the tournament resumed the following day.

The Main Event

The main event was held in the lavish Galicia Conference and Exhibition Centre, where the contest occupied a large section of the main hall and was visible to all conference attendees. This time, the event allowed connection to remote computers, allowing the most powerful computing resources to be brought into play. The winner would be competing at the very highest level of chess achievable with modern computing power.

The main event, in the Galicia main entrance hall

The contest was staged in the open entrance hall of the Galicia Conference and Exhibition Centre, enabling delegates to wander over and watch the games at any time. It served as a central showcase for the entire conference, a very public tournament where delegates drifted in and out between matches and AI sessions. The main hall made for an impressive setting.

John Hamlen (Tech 4) vs Charles Roberson (Ares)

The ICGA was scheduled to host a live online presentation on the Wednesday — the third day of the conference and the fifth day of competition. The ICGA had been allocated a room for this, and I visited it in advance to ensure I could find it. I noticed that presentations were generally held in either single or double-sized rooms, and the ICGA had been given a single-sized space. Concerned that this might be insufficient for such an historic, live-streamed event, I raised the issue with Jaap van den Herik, the incoming ICGA president. We reviewed the room together and agreed it deserved a larger venue. We wandered into the main hall and raised this with the organisers to test whether any swap was possible. To our surprise, they agreed, and a better room was quickly arranged. This was on the Tuesday, just one day before the presentation, which caused a minor panic as the new room needed to be tested to ensure it could handle a live transmission. That uncertainty lingered until Wednesday morning, but in the end, the system worked well, and the upgraded venue proved much more suitable.

By this time, the pioneers had begun arriving — some not until the third day of the conference to coincide with the ICGA session. These included three from the very first World Championship in 1974: V.L. Arlazarov, part of the winning Kaissa team; Don Beal, author of Beal; and Monty Newborn, author of The Ostrich.

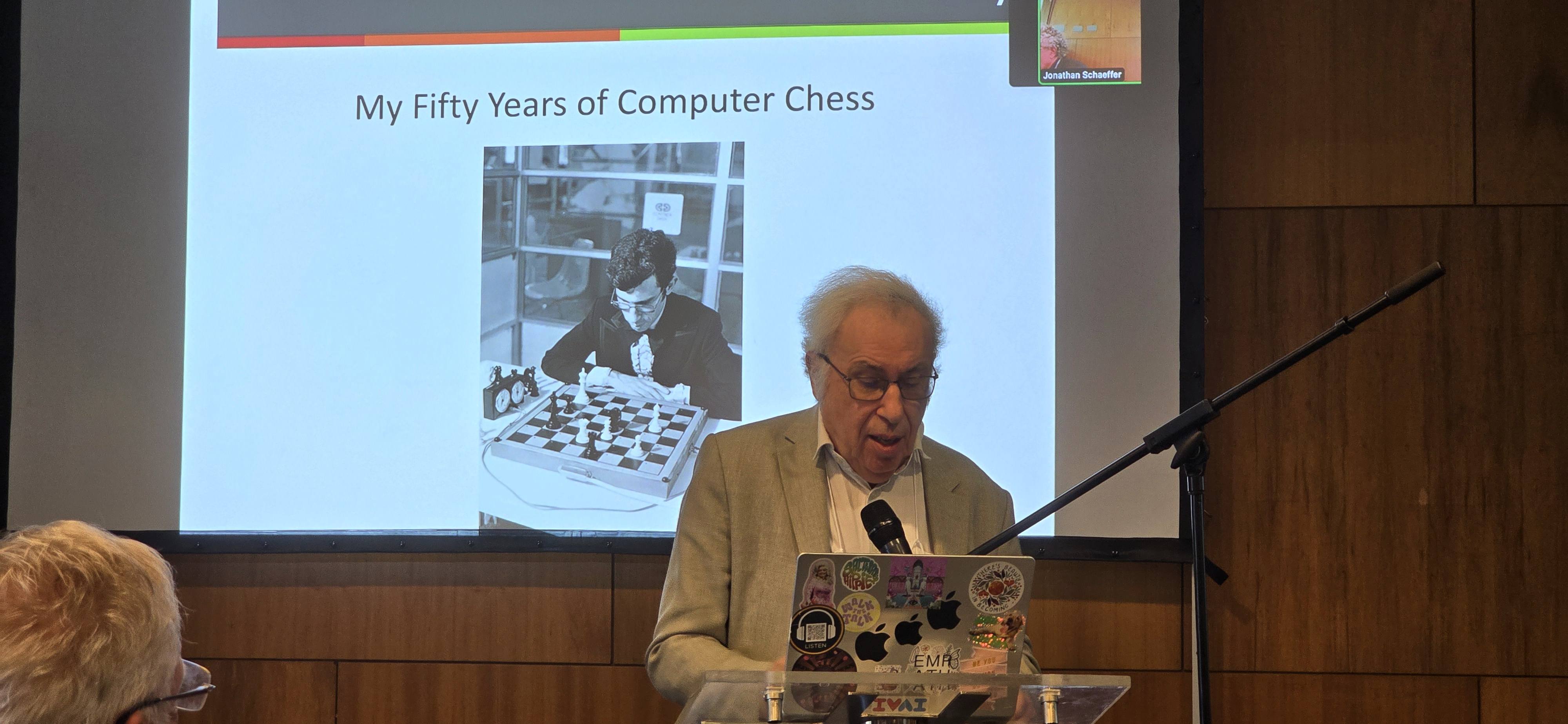

The first presentation was delivered by Jonathan Schaeffer, offering a sweeping historical overview of the event and its significance. Other pioneers who spoke included Professor Tony Marsland, who had competed in later world championships with his programs WITA and AWIT; Tom Truscott, whose Duchess had played in the 1977 World Championship and multiple earlier US ACM tournaments, starting in 1970; Murray Campbell and Feng-Hsiung Hsu, both key figures in the creation of Deep Thought (winner of the 1989 WCCC) and Deep Blue, which famously defeated Garry Kasparov in 1997; Richard Lang, creator of the microprocessor-based Chess Genius and Mephisto; and Jaap van den Herik, who presented his overview of computer games development. Finally, bringing the narrative up to the present day, Nenad Tomasev spoke on the development of AlphaZero.

The presentations concluded with David Levy reflecting on his 50 years in computer chess. The whole session had provided anecdotes from 1974 and from other parts of early Computer Chess history, which brought the history to life. 1974 really was a long time ago! As was quipped outside the session, the vast majority of delegates to ECAI had not yet even been born by then.

David Levy concludes the event with his overview of 50 years in Computer Chess

It was a well-attended and an engaging session. As expected with so many speakers and such a broad agenda, the schedule overran, leaving no time for the intended final panel discussion.

The video recording of the event is available online, and it is well worth watching, but it is long! My colleagues back in the UK tuned into the live stream and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Making the whole event work was a considerable challenge, and much credit is due to Jonathan Schaeffer for the preparation and smooth running of the programme. It was a highly satisfying and worthwhile occasion.

After the presentations, we gathered for an ICGA dinner, where awards were given, thanks offered, and conversation flowed freely. Once seated, there was an uninterrupted opportunity to talk with those beside you — in my case, Charles Roberson, author of the competing program Ares, and Don Beal, author of Beal in the 1974 tournament. It was a very pleasant and interesting evening.

The main tournament continued until Thursday. Given the symbolic nature of this final event, it was fortunate that the field had been expanded to nine competing programs, compared to just four in 2023. This broader line-up created a wider spread of strengths and helped reduce the number of draws. The main event produced 34 wins and 38 draws, compared to just 6 wins and 42 draws in the 1973 WCCC.

Competitors and attendees on the last day

In the end, the WCCC title was shared in a three-way tie between Stoofvlees (Gian-Carlo Pascutto), Jonny (Johannes Zwanzger), and Raptor (Frédéric Louguet). This result underlined the notion that the top level play indeed had now gravitated to the likely theoretical outcome of chess, a draw. Future such events under the same conditions would probably just continue to replicate this type of result, already achieving an essentially near optimum super-human level of play.

The WCCSC was won by Stoofvlees, while the WCSCC (World Computer Speed Chess Championship) went to Raptor. With these contests pegged with lower resource and time, the chance of a decisive outcome was always greater, but future such contests might also be expected to also tend to drawn outcomes.

However this end point for the WCCC was not universally acclaimed. In among conversations, in hallways and in evening meals, the idea of carrying such chess contests into the future was raised. One variation in this was proposed, to move to Fischer/Chess 960/Freestyle chess, which essentially eliminates the opening book, offering a wider richer variety of play possibilities. The underlying AI might be essentially similar, but offering a wider challenge. Fischer/Chess 960/Freestyle chess also has some significant public traction, promoted by the likes of Magnus Carlsen and attracting large audiences and prize money in human competition, second only to chess. The desire for chess to still have some role in international computer competition is still there.

The full record of the tournament and the event as a whole is available online.

This was a very important historical event, both in the history of AI and in the personal history of those that had shaped this important period. For many of us it was a great opportunity to finally meet in person the players who had shaped Computer Chess over these decades. The mantle to carry AI to the next stage now moves on to newer methods, technologies and domains.

Many thanks to Jonathan Schaeffer for organising this and drawing so many important people to the event. I was very glad indeed that I could be there!

Footnote

Computer chess, of course, did not begin in 1974. Its roots trace back to Alan Turing, who in 1948-49 designed a program called Turochamp, which executed a set of rules to play chess using a primitive minimax search, basic evaluation, and manual pruning. This was followed by a hand-simulated version, laborious to execute, but demonstrating the principle that a set of rules could be applied to play the game.

In 1950, Claude Shannon published his first theoretical paper on chess, Programming a Computer for Playing Chess, in which he defined Type A "brute force" search and Type B "selective search" principles. His paper became the foundation for the first executable chess programs on computers, with most programs developed between 1950 and 1970 referencing his work.

The first meaningful chess program was Mac Hack VI by Richard Greenblatt, which in 1966 was strong enough to defeat average club players. From there, there was an explosion of new chess programs, running on increasingly faster hardware, leading up to the inaugural 1974 WCCC.

It is worth noting how different computer hardware was at the time of the 1974 WCCC. These machines lacked many of the features we take for granted today. For example, the minimax search algorithm is essentially built around recursion, which depends on the existence of a hardware stack. Most machines at the 1974 event had no such stack — recursion had to be emulated. On a CDC 6600, calling a subroutine required the processor to store the return address at the start of the subroutine code. Automatic recursion was, in effect, impossible.

Bizarrely, there were also computers at the time that had only a hardware stack and no general-purpose memory or registers at all, such as the Burroughs B5000-illustrating the curiously divergent approaches to machine architecture back then.

The point here is that chess program development was highly constrained by the capabilities of the target hardware. Programmers needed a deep understanding of the machine itself in order to succeed. This contrasts sharply with modern times, where code written in a high-level language can be migrated to almost any device with little concern for the quirks of the underlying hardware. Optimisation is largely handled for us by hardware caches and optimising compilers. We can switch approaches and test performance with ease, without lengthy turnaround times. In short — we have it easy!

Early hardware was also far more vulnerable to failure. Reliability often depended on elaborate cooling systems. Overheating could cause computers to fail simply through the expansion of circuit boards or components. When I worked at the University of London Computer Centre (ULCC), one of the building's most notable features was the huge vent of steam issuing from the roof — haunt of flocks of pigeons — which was essential just to keep the CDC 6600 cool enough to run. The cooling system alone was a substantial part of the computer's total cost.

Cooling issues persisted for years. Early Pentium-based microcomputers were still prone to overheating, with many failures linked directly to thermal problems. Modern Intel and AMD chips now have sophisticated cooling solutions, and while the issue remains, it is now far more controlled.

All of this underlines just how much we should admire the pioneers of computer chess. They had to work far harder to achieve their goals, accomodating the hardware quirks, battling slow, failure-prone hardware and limited access to the machines themselves. Consider the ULCC, which served the entire south-east of the UK's Universities and polytechnics — its total processing power was less than a tenth of that in a single cheap modern mobile phone. That is not much CPU power to share among so many institutions.

Final note: This event was run under the auspices of the ICGA, which organises events and publishes a respected journal. I have been a member for some 45 years. It is an excellent place to connect with the AI games community, and I would strongly encourage anyone interested to take a look.

Jeff Rollason - October 2024 - August 2025